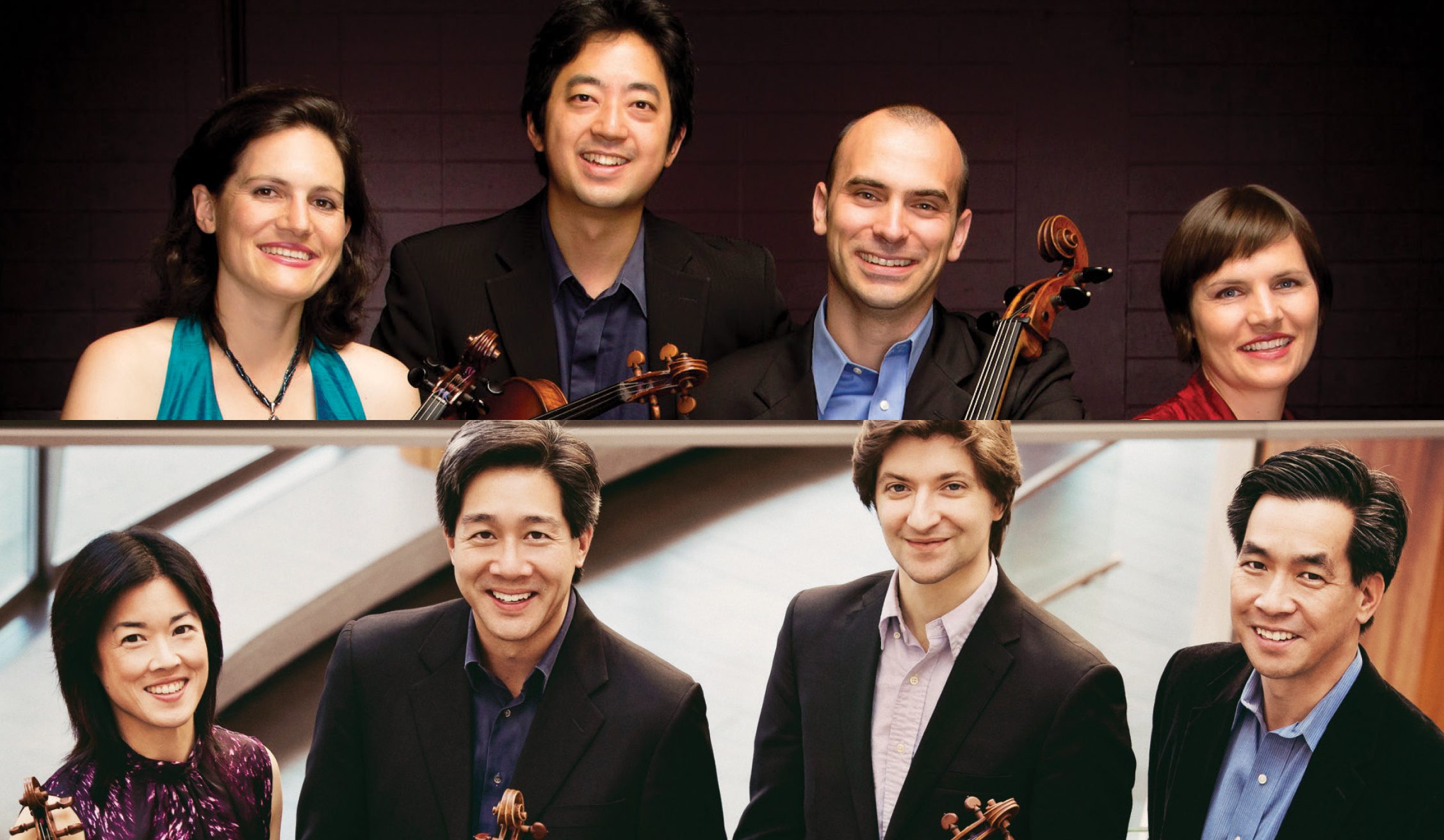

Jupiter & Ying Quartets: July 23, 2018

We happily welcome the Jupiter String Quartet back to the Festival, joining the Ying Quartet for this double-feature. The opening viola quintet is Mozart’s transcription of an earlier Serenade for winds; the string arrangement brings rich depth to this introspective work. Next, we’ll hear the sextet which opens Strauss’s final opera, Capriccio, frequently performed as a standalone concert work. Finally, no double-quartet program would be complete without young Mendelssohn’s Octet, allowing each performer to relish exuberant musical conversation and virtuosic counterpoint.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

String Quintet No. 2 in C Minor, K. 406

During the second half of the eighteenth century, it became popular for the Austrian aristocracy to maintain so-called “Harmonie” bands. Consisting of pairs of wind instruments, these bands typically provided unobtrusive, courtly music to accompany dinner banquets or outdoor gatherings. Given the ambiance of these settings, Harmoniemusik was generally kept light-hearted, often in the form of a “serenade” or “divertimento”. Mozart composed a number of works for such ensembles, often marking special events for the nobility or in the life of the city.

The String Quintet No. 2 began its life as Serenade No. 12 (K. 388) for wind octet, and is presumed to have been composed in 1782 or 1783, a time when Harmoniemusik as at its most popular. Yet given its dark key and striking intensity, it seems unusually emotive for a piece of background music, and the occasion for which the Serenade was originally composed is no longer known.

In the spring of 1787, Mozart returned to this serenade and transcribed it for string quintet, one of three string quintets he composed in quick succession. Given that the other two works constituted original compositions, it seems curious that Mozart should have decided to rework his Serenade for this ensemble. Perhaps he considered the string ensemble and chamber music setting as more appropriate than the outdoor Harmonie band for such stormy musical materials; or perhaps Mozart was short on time during this period, given his focus on Don Giovanni, and used the transcription as a way to economize, as has been suggested by Richard Wigmore. Whatever the case, the gravitas of the music suits the quintet instrumentation, with its rich, double violas – the ensemble chosen by Mozart for his most ambitious and formidable chamber works.

RICHARD STRAUSS

String Sextet from “Capriccio”

Strauss completed Capriccio in 1942. He had hatched the idea for it, along with his friend, the writer Stefan Zweig, in the previous decade; however, the Nazi government made a formal collaboration with Zweig, who was Jewish, impossible, and Strauss had to find a series of alternative librettists. With Capriccio, Strauss, then in his late seventies and with an illustrious career behind him, sought to cap off his operatic legacy with a fitting culmination of a life spent in the theater: he aimed, as he put it, “to do something unusual, a treatise on dramaturgy, a theatrical fugue.”

The resulting work is a complex, meta-theatrical opera-within-an-opera, filled with fun and philosophy. At her château in eighteenth-century France, the Countess Madeleine is courted by two rivals: the composer, Flamand, and the poet, Antoine. The ensuing conflict between the two suitors mirrors the age-old operatic debate: which is greater – poetry, or music? Over the course of the opera, theater directors, actors, and even a prompter, each make the case for their own essential role, while the countess remains thoroughly torn. As the opera commences, the curtain rises to reveal the characters listening to this string sextet, “newly composed” by Flamand for the occasion of Madeleine’s birthday, in what is actually Strauss’s recreation of an aristocratic chamber music setting in his own rich harmonic idiom.

The Sextet is frequently heard as a standalone work; and it was in fact performed that way before the premiere of the opera itself, as a personal courtesy from Strauss to Baldur von Schirach, the governor of Vienna, who promised to protect Strauss’s family (in particular, his Jewish daughter-in-law) – provided that Strauss not speak out publicly against the Nazis.

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

Octet in E-flat Major, Op. 20

Even if we disregard the age of the composer, Mendelssohn’s Octet stands as an astounding achievement. Haydn, as the tale goes, clung to string quartets since he “could not find the fifth part”; Mozart “found” the fifth part in his late quintets, but did not venture further; and Louis Spohr, whose first octets were published during the same decade as Mendelssohn’s, conceived of his as “double quartets” – performing antiphonally – rather than as a unified ensemble. Mendelssohn, however, composed for eight irreducible voices, expanding possibilities of counterpoint, texture, and interplay, allowing an orchestral richness of sound to enter the intimate habitat of chamber music. The novelty of the ensemble is demonstrated in Mendelssohn’s note to performers: “It is to be played in symphonic style by all the instruments; the pianos and fortes must be very precisely differentiated and be more strongly emphasized than usual.” And the innovations of the Octet are not limited to instrumentation: listen for the return of the Scherzo in the Finale, superimposed against the unison theme, in what is one of Mendelssohn’s first experiments with cyclical form.

These feats are all the more extraordinary in light of the fact that Mendelssohn composed the Octet at the age of sixteen. Mendelssohn’s childhood precocity, most frequently on display at the weekly musicales held in his family home, invited no shortage of attention, with frequent, inevitable comparisons between Mendelssohn and another young virtuoso from the previous century. When Goethe, who had heard seventeen-year-old Mozart play, went to hear Mendelssohn at age twelve, he wrote that “Mendelssohn bears the same relation to the Mozart of that time that the cultivated talk of a grown-up person bears to the prattle of a child.”

The Octet remained, according to Mendelssohn, “my favorite of all my compositions”: he would frequently participate in performances of it, usually playing viola, and would also orchestrate the Scherzo for concert settings. He later recalled, “I had a most wonderful time writing it”; his enjoyment is contagious, as the whirlwind of thematic interplay among the eight instrumentalists makes the Octet among the most delightful treats in the repertoire for musicians to perform and thrilling for audiences to witness.